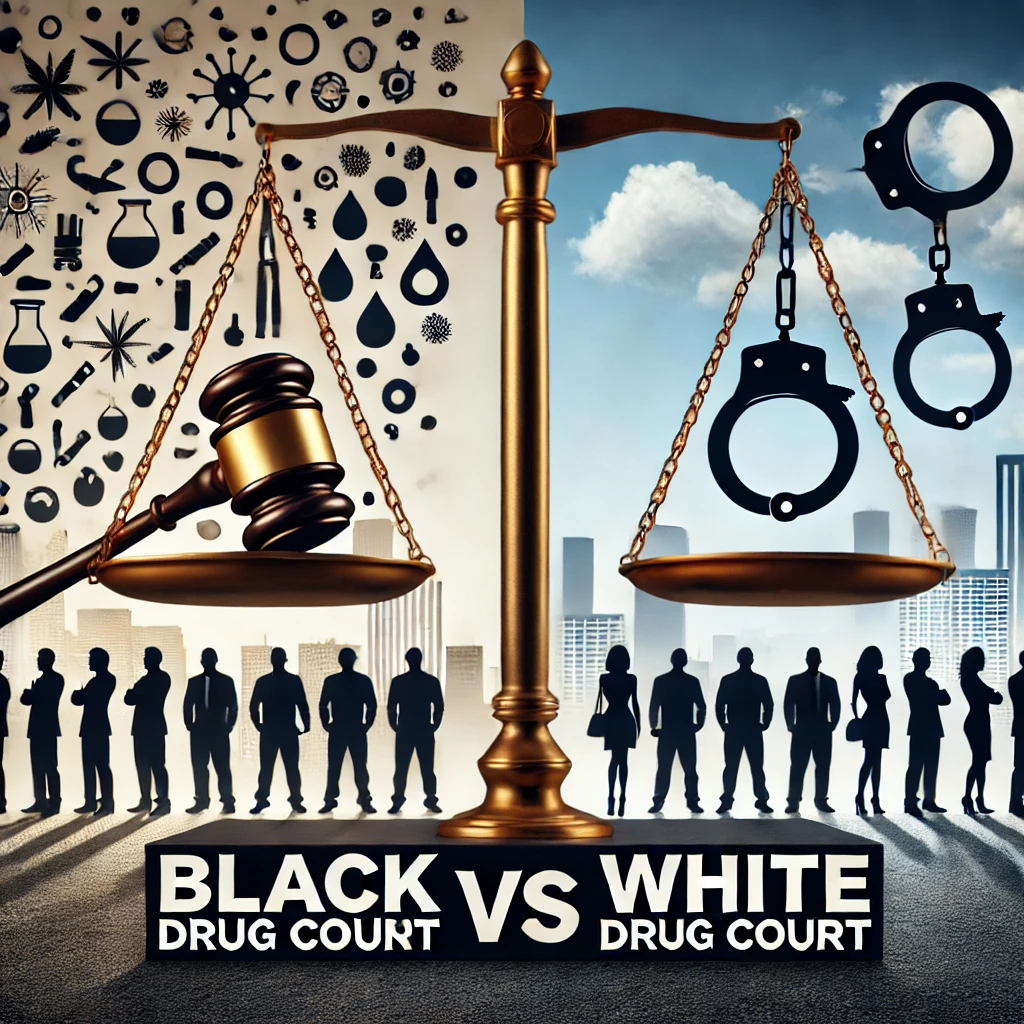

Drug courts were introduced in the late 1980s as an alternative to incarceration, offering non-violent drug offenders treatment instead of prison time. While the intent was to address addiction through rehabilitation, the implementation and outcomes have varied significantly between Black and White populations.

Most people did not know that there were Drug Courts specifically put in place to deal with the war on drugs in the ghettos which largely by design were occupied by the Black Community. We did this research to show the comparison of how these courts compared in their sentencing between the black and the white population, particularly now that we see the opioid pandemic is being classified as a health crisis and not a criminal crisis as it was for the black community.

Implementation and Racial Disparities:

- Access to Drug Courts:

- White Populations: White offenders have had greater access to drug courts, often receiving treatment programs instead of incarceration. This approach aligns with a public health response to the opioid crisis, which has predominantly affected White communities.

- Black Populations: Black offenders, however, have been less likely to be diverted to drug courts. Systemic biases and unequal access to resources have led to more Black individuals facing traditional criminal justice processes, resulting in incarceration rather than treatment.

- Outcome Differences:

- White Populations: Participants in drug courts who are White often receive more comprehensive support, including access to better-funded treatment programs and follow-up services. This has led to more favorable outcomes in terms of reduced recidivism and improved long-term recovery.

- Black Populations: Black participants face challenges such as underfunded programs, cultural biases in treatment approaches, and higher rates of sanctions within drug courts. Consequently, their outcomes tend to be less favorable, with higher rates of recidivism and continued interaction with the criminal justice system.

Statistical Data on Incarceration Rates:

- Historical Context:

- 1980s-1990s: During the height of the War on Drugs, incarceration rates for Black Americans skyrocketed due to mandatory minimum sentences and the aggressive policing of drug offenses, particularly for crack cocaine. The introduction of drug courts did little to mitigate this trend for Black individuals, as they were less frequently diverted from traditional sentencing.

- Current Context:

- Incarceration Rates (Then vs. Now):

- 1980s-1990s: Black Americans were incarcerated at rates significantly higher than White Americans, with Black men being disproportionately affected. For instance, by 2000, Black men were incarcerated at a rate of 3,457 per 100,000 compared to 449 per 100,000 for White men.

- 2020s: While overall incarceration rates have decreased, disparities remain. As of the latest data, Black men are still incarcerated at a rate of 1,630 per 100,000, compared to 678 per 100,000 for White men. Although drug courts have expanded, the racial disparities in access and outcomes mean that Black individuals are still more likely to be incarcerated than their White counterparts.

- Incarceration Rates (Then vs. Now):

Conclusion:

Drug courts have the potential to reduce incarceration rates by addressing substance abuse through treatment. However, systemic biases and disparities in access mean that Black individuals are less likely to benefit from these programs compared to White individuals. Despite a general decrease in incarceration rates, the legacy of the War on Drugs continues to impact Black communities disproportionately, with long-lasting effects on social and economic well-being.

To achieve true equity, it is crucial to address these disparities by ensuring equal access to drug courts, culturally competent treatment programs, and addressing the underlying biases within the criminal justice system.